|

Early Anglo-Saxon Clothing

Lesson #5: Page 9

Jewellery, Footwear and

Accessories: Making Simple Jewellery.

Below

are details of how to make a few types of basic jewellery – annular brooches,

wrist-clasps, strap-ends and buckles. The principles

shown for these can be applied to some of the other items of jewellery

too if you’re feeling ambitious, such as belt-mounts, girdle hangers, simple

disc brooches, etc. The tools needed are fairly basic, and

the instructions assume a basic knowledge of their use. Below

are details of how to make a few types of basic jewellery – annular brooches,

wrist-clasps, strap-ends and buckles. The principles

shown for these can be applied to some of the other items of jewellery

too if you’re feeling ambitious, such as belt-mounts, girdle hangers, simple

disc brooches, etc. The tools needed are fairly basic, and

the instructions assume a basic knowledge of their use.

The materials needed are generally brass/bronze

and iron/steel in sheet and wire form. This may be available

from hardware stores, although I usually find model shops that carry model-engineering

supplies are the best source. You will also need small iron

tacks (carpet tacks), a few iron nails and brass or steel rivets (NOT the

two part rivets).

Tools

Hammer

Files (Needle and/or warding)

Drill

Snips

Pliers

Vice

Propane burner (plumber’s type, available

from most hardware stores)

Punches (see below)

Scriber

Hacksaw

Useful tools, but not essential

Angle-grinder

Soldering iron

Small anvil

Making Simple Punches

Many pieces of Anglo-Saxon metalwork

were decorated with punched or stamped decoration. The punches

are easily made by getting cheap nail-punches or centre-punches from a

hardware shop. You can use a simple centre-punch for dots and

other shapes can be made by grinding the desired shape on the tip (again,

the angle-grinder with a sanding disc works well, as does a bench grinder,

or simply patience and a hand file). For the crescent shaped

punch-marks often seen an annular punch is used at an angle.

You now have a simple punch.

If you have access to a good gas torch

this job can be made easier by heating the tip to a dull red and allowing

it to cool slowly. Once you have shaped the tip it can be re-hardened

with the torch by re-heating up to a straw colour (a change in the surface

colour, not glowing) and then quenching in oil.

To actually stamp the design place the

brooch on a hard metal surface (The flat back of a vice, a piece of old

railway track or a small anvil all work well), place the tip of the punch

on the brooch and tap lightly with a hammer – and there you have your punched

decoration. If you wish to make a raised boss, place the item

face down on a piece of wood and use the centre punch from the back.

Annular Brooches

Annular brooches remained in use throughout

the Pagan Anglo-Saxon period, and although many were cast, a large number

were simply made from sheet material. This is very fortunate

for us, as these simple sheet metal brooches may be made easily and cheaply.

Annular brooches were usually used in pairs for fastening the woman’s gown.

The annular brooch consists of a flat

ring with a hinged pin across the central hole. The fabric

is pulled through the hole then pierced by the pin. The sheet

metal variety of annular brooches are generally around 3-6cm in diameter,

with the ring being about 1-1½cm wide. They are usually

about 1-1½mm thick, although a few are as thick as 3mm.

Decoration usually consists of punched dots (round, annular or triangular)

and/or scored lines.

To make your annular brooch:

Take a piece of bronze/brass sheet

of the appropriate size and mark two circles, one inside the other.

If you are making a pair, fixing the two sheets together with double sided

tape works well (I’m pretty sure this is not how the Anglo-Saxons did it,

but it works!) Once you have marked out the shape, remove the

centre by drilling a series of holes (as shown in fig. 2.) and then clean

the hole up with a file. The outside curve can be shaped by

cutting with tin-snips, filing or grinding (I would recommend an angle-grinder

fitted with a sanding disc for this job). Having got your basic

ring, either drill a hole or file a notch for the pin.

|

|

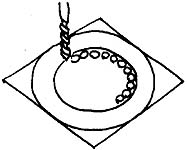

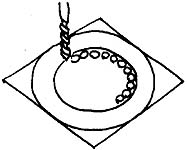

Fig. 2:

Removing the center section.

|

To make the steel pin, I would suggest

thick piano wire. Make the pin by winding the wire around

a nail, then snip it off as shown in fig. 3. Grind or file

a point onto the pin.

|

|

Fig. 3:

Wind pin around a nail and then remove excess wire.

|

You will probably find it easiest to

decorate the brooch before fitting the pin. Simple straight

lines can easily be made with a scriber or the edge of a small triangular

file. Stamped dots, triangles and rings, etc. can be

added with a simple steel punch. When you have finished decorating

the brooch, polish it and fit the pin. This is best done by

pushing the pin through the hole (or over the filed notch) from the back,

then using a pair of pliers to close the loop of the pin tightly.

And there you have it, your first Anglo-Saxon annular brooch.

Don’t worry if your first attempt seems a little crude or uneven, many

of the originals were too, and of course it doesn’t take much practice

before you start getting much neater results.

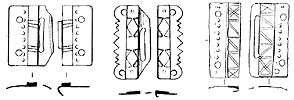

Wrist Clasps

Wrist clasps are one of the distinctive

items of Anglian women’s dress in the pagan Anglo-Saxon period, and although

many were cast, many were simply made from sheet material.

To make your wrist clasps:

|

|

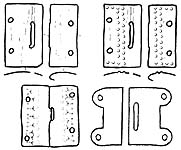

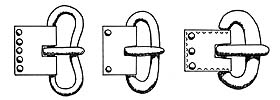

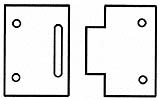

Fig. 5

|

1. Take a piece of bronze/brass

sheet of the appropriate size, ½-1mm thick, and mark it out as shown

in fig. 5. This type of clasp is generally between 25 and 40mm

long and 15 to 35mm wide. Cut out the basic shape with snips.

2. To make the slot drill

a series of small holes along the length of it then clean the hole up with

a file. At this stage you should also drill the holes at the

back edge which allow it to be sewn to the garment.

3. The plates can now be

decorated. Simple straight lines can easily be made with a

scriber or the edge of a small triangular file. Stamped dots,

triangles and rings, etc. can be added with a simple steel punch.

The back edge is also often filed into decorative curves or triangles (see

figs. 4, 6 & 7 for ideas).

4. When viewed end on the

clasps were usually slightly curved. To get this curve, gently

bend

it around a tin can or other curved object. If necessary gently

tapping it with a wooden or rubber mallet will help.

5. Finally, bend the tag

to shape and file off any rough edges.

And there you have it, your first Anglian

wrist-clasps. Don’t worry if your first attempt seems a little crude or

uneven, many of the originals were too, and of course it doesn’t take much

practice before you start getting much neater results.

The next step…

|

|

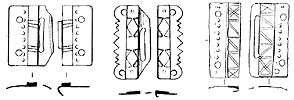

Fig. 6:

Sheet-metal wrist-clasps with applied decoration.

|

Once you’ve mastered the basics, you

might like to try a slightly more complex version. Many of

these clasps had a strip of applied decoration on them. This

is one of the commonest types of wrist-clasp and is very straightforward

to make. Follow steps 1-3 as above. Then, to make

the applied decoration, simply cut a strip the same length as the clasp

and about 4-6mm wide. This may be the same thickness as the

clasp itself, but more usually were somewhat thicker (about 1½-3mm

thick). Decorate this by filing and punching (as above) and

when it is finished, solder it in place along the leading edge of the clasp.

Once this is done, finish it off as above.

|

|

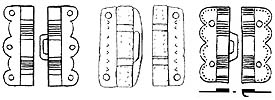

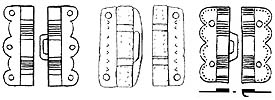

Fig. 7:

Sheet-metal wrist-clasps with applied decoration.

|

Even more advanced…

|

|

Fig. 8:

'E' shaped wrist-clasps.

|

Another fairly common type of wrist

clasp was the ‘E’ shaped variety. These are a little more complex

to make, but still not difficult. For this you will need thicker

brass/bronze, approximately 2-3mm thick.

1. Cut a rectangle of the

appropriate size. You’ll need a hacksaw to do this.

2. File or grind it to

the section shown in fig. 9.

|

|

Fig. 9

|

3. File the tags to shape

and then file in the decorative grooves.

4. Drill out the slot and

the holes for attaching it to the dress.

5. Make the hook from a

small piece of sheet, solder it to the clasp and bend it to shape.

So there you have three different types

of wrist-clasp of varying levels of complexity, but all possible to make

with basic tools.

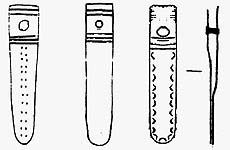

Strap-Ends

Strap-ends formed a fairly common part

of Anglo-Saxon dress, and although many were cast, many were simply made

from sheet material.

To make your strap-ends:

1. Take a piece of bronze/brass

sheet of the appropriate size, ½-1mm thick, and mark out two tongue-shaped

pieces (see fig. 10). This type of strap end is generally between

25 and 55mm long and between 8 and 15mm wide. Cut out the basic

shape with snips.

2. If you are going to

decorate the strap end, take one of the pieces and decorate it by filing

and punching, then make sure the reverse is smooth by filing/sanding.

3. Solder the two plates

together, leaving the top unsoldered to create a split. The

length of this split varies, usually being about 10-15mm, although in some

cases the split can be more than half the length of the strap end.

Once it has been soldered drill a small hole to allow it to be riveted.

4. Clean up any rough edges

with a file, and then carefully open the split a little. Place

the end of your belt/strap into the split, squeeze the strap end to close

it onto the belt, then secure it with a small rivet (a small carpet tack

mages a good rivet for this purpose).

And there you have it, your first strap-end.

Don’t worry if your first attempt seems a little crude or uneven, many

of the originals were too, and of course it doesn’t take much practice

before you start getting much neater results.

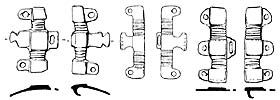

Buckles

Anglo-Saxon buckles come in many shapes

and sizes, with many variations through the period. Luckily,

one of the simplest types with a simple oval loop and plate remained in

use throughout the early Anglo-Saxon period.

To make your buckle:

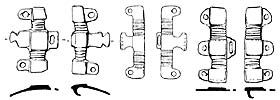

|

|

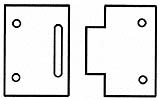

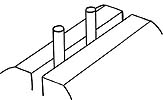

Fig. 12

|

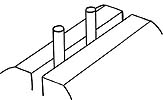

1. Place two nails or metal

rods in a vice as shown in fig. 12. The size of the rods and

their spacing depends on the size of buckle you are intending to make.

2. Take a piece of iron/brass/bronze

rod somewhat longer than twice the length of the distance across the two

rods from step 1. The diameter of this rod should be in proportion

to

the size of the buckle (see fig. 11 and the photographic examples to get

an idea of these proportions). For larger buckles it is an

idea to narrow the ends slightly. This can be done by filing,

grinding or hammering (or if you are feeling brave, by clamping the rod

in a drill and using it as a simple lathe).

|

|

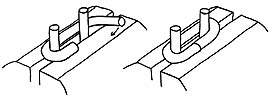

Fig. 13

|

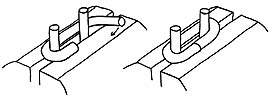

3. Heat the rod and while

it is still soft, bend it around the two rods as shown in fig. 13.

It is easiest to do one end at a time. If you find the two

ends overlap, do not worry, simply trim them with a hacksaw the finish

aligning them. At this sage you might wish to bend the leading

edge to make a kidney-shaped loop. You can also solder (or braise

or weld, depending how adventurous you are feeling) the ends together at

this stage if you wish.

4. To make the pin take

a piece of rod or a nail (even on bronze buckles iron pins were often used).

You can flatten the back by filing to produce a half-round section, or

hammer the whole thing to produce a flat-sectioned pin. Whichever

method you use, flatten one end of the pin completely, then bend this around

the back shank of the buckle. If necessary, cut the front end

of the pin to length and clean up any rough edges with a file.

5. To make the buckle plate

take a strip of bronze/brass/iron sheet (it need not be the same material

as the buckle-loop) the same width as the belt and fold it in half.

Folding it around a shank of similar diameter to the buckle is sensible.

File a slot halfway along the folded edge for the pin to pass through.

The plate can now be decorated if you wish. Simple straight

lines can easily be made with a scriber or the edge of a small triangular

file. Stamped dots, triangles and rings, etc. can be added

with a simple steel punch.

6. Fit the plate over the

pin and around the buckle-shank. To fix it to a belt put the

end of the belt between the two halves of the buckle-plate and then drill

and rivet it in place. The number and arrangement of rivets

varies considerably.

And there you have it, your first Anglo-Saxon

buckle. Don’t worry if your first attempt seems a little crude

or uneven, many of the originals were too, and of course it doesn’t take

much practice before you start getting much neater results.

Page

1 | Page 2 | Page

3 | Page 4 | Page

5 | Page 6

Page

7 | Page 8 | Page 9 | Page10

| Page 11 | Page 12

Bibliography

|