|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lesson #5: Page 5

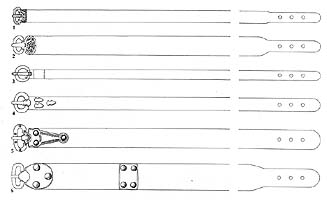

Buckles

Click on Image for larger version in new window

Technologically the buckles tend to fall into several main groups, those with cast plates; those with a cast openwork frame in which the central void is filled by a sheet-metal insert; those with sheet-metal buckle-plates; those with no plates at all (although some have lost their plates since manufacture, in many instances there never was any plate); and those in which the plate and loop are produced as a single rigid casting to which only the moveable tongue (and, in some cases, a back-plate) had to be added. Many of the cast buckles are provided with perforated lugs projecting from the back of the plate: these are designed to pierce the material of the belt and to project through a corresponding set of holes in the back plate; pins passing through the perforations originally held the assembly together. More common as a method of securing the buckle to the belt is for a set of rivets to be driven through the whole assembly. On cast buckles the head of these rivets was often expanded to form domed bosses, whose ornamental effect may be enhanced by interposing a washer with a ribbed periphery that formed a decorative collar to the rivet-head. Occasionally these ribbed collars were integral with the rivet heads. In some buckles with cast plates, the hinge is formed by sets of perforated lugs projecting from the end of the plate and front loop respectively; these are united by a separate axis pin, which may be made of iron or of copper-alloy. Alternatively, the hinge may be formed by folding a sheet-metal extension from the buckle-plate (or, indeed, the entire buckle-plate in the case of sheet-metal examples) around the captive end of the loop. The tongue, with which the belt was fastened, may be anchored to the buckle simply by having its end wrapped around the loop. Alternatively, it may have a separate anchorage cast on the back, in the form either of a perforated lug or of a projecting spike designed to be bent around the loop to fix it in place. A commonly encountered decorative feature, particularly in the sixth-century, is for a shield-shaped boss to be cast as an integral part of the base of the tongue, in some case set with a garnet or other inlay. In other cases the tongue itself is given some cursory zoomorphic treatment. Iron tongues were often fitted to non-ferrous buckle loops. As for the buckle-loops themselves, the simplest forms are oval rings without further modification, whilst others are enhanced with cast, punched or incised decoration. The captive end may be thinned and rounded to enable it to swivel more easily; some examples are stepped to form a distinct hinge or axis about which the buckle-plate and tongue may pivot, while some of the more massive copper-alloy loops have an axis in the form of an inserted iron pin. The surfaces of many of these massive loops display traces of tinning, some so thick as to form an applied foil. Buckles with simple oval loops are used throughout the period, usually with a square or rectangular plate. Some of the loops tend to be almost round, whilst others are almost D-shaped, with the majority being a pronounced oval with fairly straight sides. They vary considerably in size with some as wide as 2” (5cm) and others as small as ½” (1.2cm). A number of buckles of late Roman type (along with other associated fittings) are known from the fifth-century, and despite their Roman origins their Anglo-Saxon cultural affinities are not doubted. These late Roman types fall into three main categories. The first are the large ‘chip-carved’ buckles where the buckle loop is surrounded by a large square or rectangular cast plate covered in chip-carved decoration. These are usually 3-4” (7.5-10cm) wide, often with matching triangular counter-plates and cast strap ends. These are found exclusively in male graves and are thought to imply military status, perhaps representing Germanic mercenaries in Roman service. The next type are those where the simple loop ends in two stylized animal heads either side of the hinge, connected to a cast or sheet-metal plate, either rectangular or D-shaped, but originally fitted to much wider belts as shown by the long belt stiffeners often found in association with them. The well-known Dorchester belt set has a buckle of this type. The last type is where the loop is formed to look like two curving animals, most usually dolphins. whose mouths meet on a roundel or stud under the tongue of the buckle. These usually have rectangular plates, of cast or sheet metal construction. The loops often have projections in the form of crests or fins on the animals’ backs. Although these buckles have military connotations on the continent, many of those from England come from women’s graves. A fourth type with Roman links are those with kidney shaped loops which are of Roman military origin, but carry on into the Anglo-Saxon period. At the other end of the period are buckles with elaborate triangular plates, expanded to take three large domed rivets, appear in the sixth century and carry on into the seventh. They seem to be of Continental origin, and are most often encountered in Kent. Some were quite plain, whilst others were extremely elaborate, constructed of precious metals and inlaid with jewels. Click on image for larger version in new window

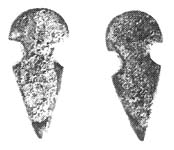

Strap Ends

Some strap-ends preserve textile remains in the split end (often tablet braid), and it seems their main function in early Anglo-Saxon England may often have been used to prevent the ends of textile belts from fraying. Of course, leather does not fray, so a strap end is not so important on a leather belt. However, some strap ends do retain traces of leather, so they were also used on leather straps, but here their function seems to have been purely decorative. It is also worth noting that strap-ends occur more often in women’s graves, perhaps indicating textile belts were more commonly worn by women than by men. These strap-ends are generally made from sheet metal, often with punched or incised decoration, or are cast, with or without decoration. The urn-shaped strap-ends seen in the fifth-century seem to belong to the same group of belt fittings as the Roman-style buckles mentioned above. The more usual shape was a tongue shape, sometimes slightly waisted. Click on image for larger version in new window

Belt Mounts

Some of the more elaborate belt-plates have the appearance of being designed as matching accessories for buckles with similarly ornamented buckle plates. Some are relatively plain, whilst others are jewelled and gilded, and are usually of cast construction. These pieces are entirely Anglo-Saxon in appearance and date to the sixth- and early seventh-century. Studs designated as ‘shoe-shaped’, characteristically rounded at one end and pointed at the other, with a pair of lunate notches to either side, are found in close proximity to the buckle itself (normally the shield-on-tongue type). They probably served to secure the buckle by folding the leather around the hinge and then piercing the double thickness with the lug on the back, which normally has a hole through which a pin passes. These mounts are usually found in pairs, though single and triple examples are also known. This type have strong Frankish affinities, and not surprisingly are most common in Kent. Click on image for larger version in new window

Keys

These items are found throughout Anglo-Saxon England, though are slightly less common in Anglian areas where girdle hangers may have served some of the key’s symbolic function. Occasionally they are founf in association with girdle hangers. Click on image for larger version in new window

Girdle Hangers

In general they have the appearance of being forged, although many examples were probably cast and often have a half round moulding near the suspension loop. The complete hangers have in common a pierced suspension loop at the top and recurved arms at the terminal in the form of a letter E, although sometimes the ends of the arms return to form a pair of rectangular or trapezoidal loops. The degree of elaboration of the basic form varies widely, as does the decoration, stamped, scribed or cut onto the front surface. All the reverses are plain, suggesting the rigid iron loops which survive at the top of some examples ensured that they always hung with the decorated side outermost. A few have perforations at the lower end, occasionally fitted with a wire ring, suggesting other items may have been attached. In distribution they are limited almost entirely to Anglian areas. Click on image for larger version in new window

Knives

Generally, knives were worn at the waist, the sheath attached directly to the belt, or suspended from it by a short strap. Härke has shown that there is a tendency for men to be buried with larger knives than women or children. Some graves contain more than one knife, a custom fairly common on the continent where it is thought that one knife would have been used for eating, whilst the second knife was used as a general tool. The blades are single-edged and triangular in section. The sharply angled back so characteristic of later Anglo-Saxon knives was less common in the early period where most knives had a straight back that curved gently to the tip. The cutting edge could be straight or could curve slightly towards the tip. A few knives, particularly the larger examples, have a fuller running down one side (or rarely both sides) close to the back. Many show signs of having been sharpened again and again until less than half the original width of the blade remains. Some had hard steel cutting edges welded onto a softer iron back, and a few of the larger examples were pattern-welded in the manner of good swords. Click on image for larger version in new window

Toilet Implements

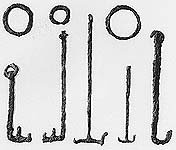

Picks are presumed to have functioned primarily as nail-cleaners, for the distinctive item developed for this purpose in the Roman period is absent from Anglo-Saxon England; the possibility they may have been used as tooth-picks has also been suggested (and in fact, where there are two picks in one set one may have served each function). In many excavation reports they are referred to as prickers, while in others they are assumed to be pins. When found threaded on a ring with an ear-scoop their toilet function is clear, but since almost identical pieces were also used as dress pins, there are instances when only the position within the grave gives any clue as to identification. Most commonly they are found in women’s graves, and from their characteristic position it is clear they were normally worn suspended from the waist. Picks are seldom of elaborate construction, normally consisting of no more than a circular- or oval-section shank, hammered or rolled rather than drawn, pointed at one end and flattened to form an expanded head at the other, perforated for suspension. The ear scoops were similar in construction, with appropriately spoon-shaped ends. Occasionally, the shanks of implements in matching sets each show similar decorative treatment. There is a striking degree of variety amongst the tweezers found in Anglo-Saxon graves, ranging from well-made (and functional) types with solidly-wrought tops and substantial examples with well formed loops, to others of thin sheet metal so flimsy that they could not have formed any practical function. Indeed the latter are invariably found with cremation burials and clearly served as ex votos in just the same way as the miniature shears and combs found in the same burials. (Both functional and token forms are also found in iron). The commonly accepted idea is that they were used for plucking body hair, although practical use has shown they serve best for removing splinters, surely a common problem to the Anglo-Saxons with their heavy reliance on wood. In some instances they are provided with suspension rings as though they hung from a girdle with other toilet implements, but the majority of those from secure contexts are from male burials, reflecting the normal practice on the continent. The decoration applied to these items is fairly rudimentary, comprising incised lines and crosses, stamped rings and lateral grooves or bevelled edges, much like that found on other metalwork such as belt-fittings. Many of the tweezers themselves come from fifth- or sixth-century contexts; some may be of Roman origin, but as a type they survive into the seventh century. ‘Scrapers’ resemble one leg of a pair of tweezers, except that the foot turns outwards and may be centrally notched to form two prongs. Although their use is obscure, their identification as toilet implements seems justifiable on account of their occasional discovery in association with other implements of more certain function. The true function of the items now thought to be cosmetics brushes, which formerly were commonly classified as needle-cases or as amulets of ‘Hercules club’ type, was first recognized by P.D.C. Brown, who drew attention to an example from Oostrum in the Netherlands, threaded on a ring along with an ear-scoop and with a tuft of hairs surviving within the tubular handle. Since then, further finds from England, where their distribution is mainly confined to Wessex and the West Midlands, have confirmed this identification. A bundle of hairs, bound together in the center, would have been drawn up into the tube by passing the binding thread through the opening at the top of the conical tube; an adhesive no doubt helped to keep it in place thereafter. Unfortunately we have no idea what type of cosmetic purpose these brushes had, as we have no other evidence for the use of cosmetics. Click on image for larger version in new window

Crystal Balls &

Perforated Spoons

Although most are of high quality, a few poor copies appear late in the sixth century. They are usually quite crude and of tinned copper-alloy and are much smaller than the high-class examples. Perhaps these were made for poorer women wanting the luxuries of the upper classes. Their use of the perforated spoons is unknown: sifting powder and straining wine have been suggested as possibilities. Written sources and archaeological evidence suggest that skimmers were used for the skimming of both pure and spiced wine in late antiquity. Wine in the 6th century was a luxury item and serving it seems to have been the privilege of certain ladies in rich households; their skimmers were not only meant for practical use at the table, but also served as status-symbols. The outstanding quality of most Kentish perforated spoons, in both materials and design, would fit in well with this idea, and might suggest that wine was even more precious in England than on the continent. (The Frankish pottery bottles imported into Kent as wine containers and found mainly in seventh-century graves often show signs of long use and repair and thus also support the idea of wine being precious.) Crystal balls were also luxury goods and high status objects. They are usually set in silver slings formed by two decorated silver bands which cross at the bottom and meet inside a small, cylindrical silver cap at the top. The cap (and the ends of one of the bands) are perforated by a silver ring for suspension. The size of these crystal balls varies from just under 1” (c. 20mm) to well over 2” (c.60mm). A frequent (but also unexplained) association of perforated spoons with crystal balls has been noted, especially in Kent where these items are most commonly found. Many women’s burials with either a crystal ball or perforated spoon are known on the continent; but in Kent both items are typically found together as female equipment. The fact that they are rarely associated on the continent means their uses (if any) may not have been related, though many modern researches have sought for a purpose they would both be used for. There is little doubt they indicate high status, but any use beyond this is uncertain. Meany and Martin suggested that the crystal balls carried with perforated spoons were also connected with wine. The Romans believed that crystal was formed by the intense freezing of snow and therefore had a cooling effect, so a crystal ball may have been believed to protect the owner from thirst and maybe also from drunkenness. However, there is no evidence that the Anglo-Saxons had the same belief, and as we have seen the crystal ball and perforated spoon need not have shared a common use. A ritual use of some kind seems likely, perhaps amuletic. Crystal balls also have a long history of use for foretelling the future, and the prophetic power of women was highly esteemed in early Germanic culture, so another kind of ritual use might also be suggested. These items generally date to the sixth century, although surviving Late-Roman strainers such as that from Water Newton in Cambridgeshire, dated to the early fourth century, suggest direct ancestors of the Anglo-Saxon perforated spoon. These roman examples may well have been wine strainers. In Anglo-Saxon contexts these items are most commonly found in Kent, and are worn suspended from the belt on long (probably leather) straps. Click on image for larger version in new window

Bags and Purses

More ornate pouches are known from the archaeological record. Wealthy women sometimes had bags, probably of textile, with an ivory ring forming a frame at the opening. This type of bag often contained keys, and seems sometimes to have been decorated with beads, spangles or perhaps iron and bronze rings, although it is not always clear whether these items were contained inside the bag, or were adorning it. It is unknown if the ivory was of African or Indian origin (although fossil ivory is ruled out due to its fragility), but it does suggest the extensive trade by Rome in both Indian and African ivory probably did not cease with the end of the Empire. The distribution in England is mainly Anglian, though they are known from most of southern England, and they range in date from the fifth to seventh century. A few pouches with kidney shaped lids,

sometimes stiffened with wood, bone, ivory or just stiff leather, sometimes

adorned with applied decoration. This type is rare, and seems

to indicate high status, although the purpose of the pouch is unclear.

The best known, and most ornate, pouch of this type is the one from Sutton

Hoo. This contained gold coins and a use for a Lord rewarding

his retainers with items from such a ‘purse’ has been suggested.

The available evidence suggests such pouches were not widespread.

This style of pouch seems to date mainly to the sixth and seventh century.

Pursemounts/Firesteels

Iron Rings

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Costume

Classroom is a division of The

Costume Gallery, copyright 1997-2001.

Having problems with this webpage contact: questions@costumeclassroom.com |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||