|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lesson #2: Page 2

Wool

The wool of such yarns has almost certainly been combed before spinning, using a pair of iron toothed combs to smooth and straighten the fibres. Wool-combs of a sort have been in use since Roman times, but a type with long handles at right-angles to the teeth first appear in Scandinavia and England in the fifth to seventh centuries (very good examples come from some high status female burials in Lechlade in Gloucestershire, and a slightly later example, still with a wool fibre adhering to the base of one of the teeth, was recovered from the Anglo-Scandinavian levels at York.) While the combed yarns can be identified with some degree of certainty, the technique used to prepare the remainder of the wool finds is not so obvious. Although some of the finest yarns are smooth and even, they lack the glossy parallel-fibred appearance of the more obviously combed yarns. Whilst such yarns may have been combed, it is also possible that a skilled spinster working straight from the wool staple could have produced them. However, the majority of yarns are soft and bulky (although often fine), sometimes with loose fibre-ends curling away from the thread. In the later medieval period these yarns were prepared by brushing the fibres with hand cards (small boards set with many fine teeth) or by gently beating the raw wool with a large bow strung with gut. Unfortunately there is no evidence for hand cards before the 13th century, or for the bow before at least the 12 century (if the latter ever reached England at all). It is possible to speculate that some primitive form of hand card, such as thistles set in a frame, or teasels, was used in the early Anglo-Saxon period, or whether the wool was only teased out before spinning. Vegetable Fibre

Flax is prepared for spinning by soaking the stems until the outer parts rot (a process sometimes referred to as 'retting'), then breaking them up by beating with a mallet or wooden chopper. The crushed stems are next drawn through iron spikes to separate the long fine fibres, which can then be spun into a smooth firm yarn. A similar process is applied to other stem fibres such as nettle and hemp. (Stem fibres are only pre-treated in this way when they are required for weaving. Ropes made from whole stems of flax have been found on some sites; this requires no pre-treatment beyond stripping off the outer leaves.)

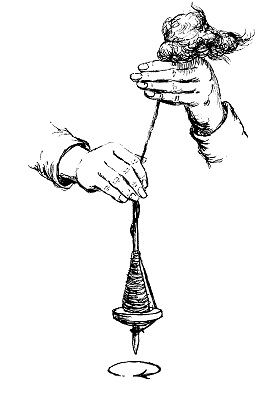

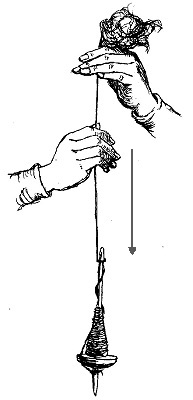

Spinning In the early Anglo-Saxon period thread was produced by the process of drop spinning. A drop spindle consists of two parts - a wooden spindle and a whorl. The whorl is effectively a flywheel to keep the spindle revolving and can be made of many materials - clay, stone, bone, even amber spindle whorls have all been found. The spindle would be spun with a flick of the fingers and the yarn drawn out from the mass of fibres with both hands. As more yarn was produced the spindle would drop down (hence the term 'drop spinning'). When the spindle reached the ground the thread was wrapped onto the spindle and the process repeated. The weight of the spindle had a big effect on the yarn produced. Generally the heavier the spindle the longer it will spin for enabling the spinner to make a longer length of yarn with each spin. A heavier spindle will allso pull the thread tighter producing a thinner thread (although if the spindle is too heavy the thread is likely to snap!) This means that generally, contrary to the popular image of 'homespun' #1 cloth, relatively thin threads were easier to produce than thick ones. It takes a very skilled drop spinner to produce a thick, even yarn with a drop spindle. The prepared wool or flax could have been put on a distaff to make it easier to spin. This is a forked stick around which the carded wool is wound. The distaff is then tucked under the arm, leaving both hands free for spinning. It was not uncommon for a single garment to require between 3 and 5 miles of thread!

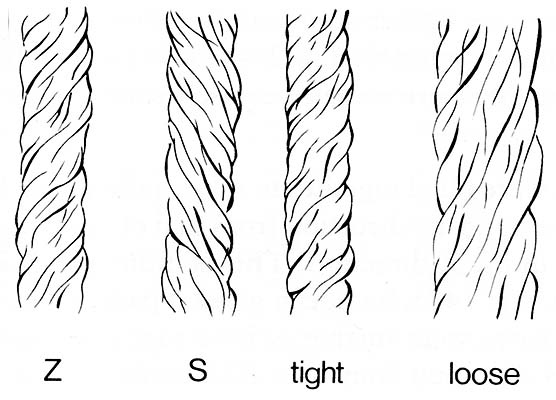

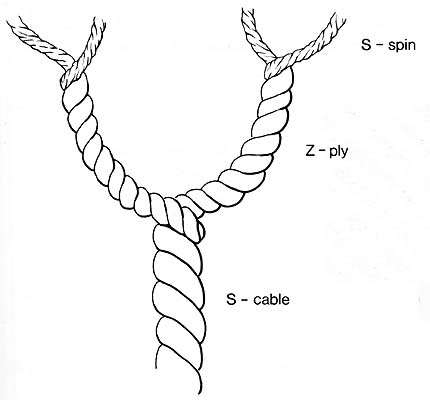

When spinning, whether a drop spindle or a spinning wheel is used, the yarn may be twisted either clockwide or anti-clockwise. Clockwise spinning produces a yarn in which the fibres lie in the same alignment as the middle stroke of the letter Z, whilst anti-clockwise follows the letter S. For this reason the two types of spinning are called Z-spun and S-spun. The spinner can also regulate the speed at which the fibres are drawn out, thus controlling how tightly the yarn is spun. In Anglo-Saxon textiles, Z-spun yarns with a regular degree of twist seem to be the norm for linen. Both Z and S, with varying degrees of twist, were used for wool. Generally the Z-spun wool yarns (often used for warp threads) were tighter spun and therefore stronger, but they were also sometimes finer than the softer S-spun weft.  Sometimes two or more threads were plied together to make a thicker, stronger yarn. Usually the twist of the ply runs in the opposite direction from that of the spin, so that two S-spun yarns will be plied together in the Z direction, for example. Some thicker cords, sometimes resembling string, were given a particularly tight twist for added strength. Some plied yarns were further twisted together to give a bulkier cord: a cabled cord twisted together in the S direction from 2 S-spun, Z-plied cords for example.

Dying After the yarn had been spun it would often be dyed using natural dyes. Dyestuffs could have been grown in gardens or fields at a settlement or collected from the countryside. The yarn would could be mordanted with alum, iron, or an alkaline solution made from stale urine. The mordanting process enables the yarn to take and keep the colours better. Woad leaves were used to give a blue, the whole of the weld plant for yellow, madder roots for oranges, reds and brick colour, lichens for purples and browns, etc.. Many other roots, berries, barks and lichens were probably used for dying too. Little is known about the exact process of dying in the early Anglo-Saxon period, and the exact colour obtained from a particular dye varies with the hardness or softness of the water, the ratio of dyestuff to yarn, the material the dyebath is made from, the natural colour of the wool used, etc. This means that a wide selection of colours could be obtained from a relatively small number of basic dyestuffs. Frther colours could be obtained by overdying - first dying the thread with one dyestuff, then redying it in a different colour. Experiments with dying using the dyestuffs and methods available to the Anglo-Saxons gives a wide range of colours, although some colours seem to be difficult or impossible to achieve. The table below gives a few examples

of colours that can be obtained fromvarious dyestuffs. Those

in italics are dyestuffs which are likely to have been used but have not

been possible to detect from archaeological remains.

As can be seen a wide range of colours were available, although cetain colours are noticable by their absence, particulary purple-reds (burgundy, etc.), deep blues, bottle-greens and black. (Some dyestuffs such as oak-galls would give a fair black at first, but are not colourfast and would soon fade to a deep brown.) 1 The coarse, uneven cloths people think of as 'homespun' tend to come from much later when thread was produced on the wheel, where (I am told by those who know) it is easier and quicker to produce a thick thread. back Page

1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page

4 | Page 5 | Page

6 | Page 7

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Costume

Classroom is a division of The

Costume Gallery, copyright 1997-2002.

Having problems with this webpage contact: questions@costumegallery.com |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||