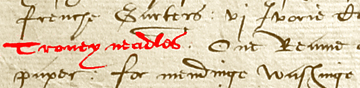

The Mystery of the Tronoy Needles

or “What happens when you take the blue research pill and find out just how far the rabbithole goes.”

In transcribing Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Accounts (I’m currently up to 1592…10 years to go!), I come across obscure terms that went out of common usage centuries ago. Some of these mystery words are fairly easy to discover. I have my go-to books for identifying Pewke, Pampilion, Peropus, Philoselle, or Paragon: Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d is first, given that it covers the same types of documents that I’m working on, and I usually have some success with it, or with the books referenced by it in footnotes.

In transcribing Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Accounts (I’m currently up to 1592…10 years to go!), I come across obscure terms that went out of common usage centuries ago. Some of these mystery words are fairly easy to discover. I have my go-to books for identifying Pewke, Pampilion, Peropus, Philoselle, or Paragon: Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d is first, given that it covers the same types of documents that I’m working on, and I usually have some success with it, or with the books referenced by it in footnotes.

If I have no luck, my next stop is usually the section on Fabrics in Costume in the Drama of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries and Stuart Press’s Textiles of the Common Man and Woman.

If I still come up empty, my next stop to roll up my sleeves and do a general Google Books search of the term. Progresses and Processions of Queen Elizabeth is now online and searchable there, as are Documents Pertaining to the Revels in the Time of Queen Elizabeth and several other obscure books on 16th century documents.

Using the odd spellings in the original manuscripts, combined with restricting Google Books search results to the 19th century, can turn up some real gems; Google Books has made once-obscure Victorian Journals like Archaeologia Cambrensis, Journal of the Yorkshire Archaeological Society and The Gentleman’s Magazine not only available, but searchable. The Victorians loved their historical documents, and loved to transcribe bits of old manuscripts and make them available to “modern” readers, sandwiched between interminable geneaological expositions and careful drawings of rural priory ruins.

Google Books is also good at introducing me to obscure books I’d never have thought to look at for sources; The Walloons and their Church, for example, is hands-down the best source on varieties and names of late 16th and early 17th New Draperies made in Norwich available.

If even Google comes up dry, I then search post-period sources for fabric names and try to trace them back from there.Textiles in America 1650-1870 is a good source, as are 1700 Tals-Textil and A Lady of Fashion: Barbara Johnson’s Album of Styles and Fabrics, two facimiles of 18th century manuscripts containing swatches of fabric and descriptions of them.

Sometimes, however, I come across a term which is obstinately, obdurately opaque. Like…

Tronoy Needles.

In the 16th century, a needlemaking revolution occurred. The discovery of how to make steel needles, long known in the orient, finally made it to the other end of the Silk Road and took root in Spain in the mid-1500s. Toledo, known for its blades, was also a center of steel needlemaking.

The first steel needles in England were imported from Spain. Eventually, spanish needlemakers brought the art to England, and a modestly-sized domestic steel needle industry was born.

One can assume that the Queen’s Wardrobe, with its deliriously large budget and consistent demand for the highest quality materials, would use steel needles. And there are a couple of references to “spanish needles” and “milan needles” (Milan needles being another high-quality type of steel needle);

The great majority of needles in the wardrobe, however, are described as “Tronoy” needles. Alternately, given the whimsical attitude towards spelling found in 16th century texts, they were known as “trony”, “troney” or “tronoye” needles.

I’d seen a lot of needles described in 16th century sources: “coarse needles”, “fine semster needles”, “great needles”,”sail needles”,”squre needles”,”holland needles”,”tailor’s needles”,”spanish needles”,”Jesus needles”,”Milan needles”,”country needles” and “steel needles”, but not “tronoy needles”.

A check of my usual books came up empty. More surprisingly, Google came up empty as well. I’d expected to find at least a breadcrumb on Google to lead me elsewhere, some 18th century quotation or probate inventory that mentioned it; but there was nothing.

I checked the other books in my library, and came up with an equally big chunk of zilch. I checked Minsheu, Cotgrave and some other early 17th century French-english and Spanish-english dictionaries, hoping to come up with some reasonably close word. But the Spanish word “trone” and French word “troigne” could not, even by the most creative leaps of the imagination, be said to have anything to do with steel or needles.

At this point, any reasonable person would give up, decide that Tronoy probably meant “spanish”, and move on to more interesting things. But I’d spent too long on this one obscure, trivial term to give up. It bugged me. Surely someone, somewhere had come across this word and written it down?

So I sat back and thought. “Cullen ribbon” came from Cologne; “Jeanes Fustian” from Genoa, and “Towers Ribbon” from tours. Tronoy could very likely be some place name, probably spanish, that had been similarly mangled by the Elizabethan English tongue.

The hours spent poring over 16th century maps of Spain, looking for any town name starting with a T that could possibly be converted into “Tronoy”, bore little fruit. “Terra Nuevo”, the only possible match, had no reference to a needlemaking industry in any of them. I checked some 16th century maps of France and Italy as well, with similar results found for Troyes and the two other possible matching cities.

There had to be something, I thought. Some clue, somewhere, as to just what the heck these stinkin’ Tronoy needles were.

So I went back to the beginning: the wardrobe accounts. I listed how many needles of what kind were bought in each 6-month warrant, and looked at the results:

| Warrant | Needles Bought |

| 1574 October | 100 Millen Needles |

| 1574 October | 200 spanish needes |

| 1575 September | 100 Tronoy Needles |

| 1576 September | 200 Tronoy needles |

| 1577 April | 200 spanish needles |

| 1577 September | 150 tronoy needles |

| 1578 September | 300 tronoy needles |

| 1579 April | 400 Tronoy Needles |

| 1579 October | 24 long spanish needles |

| 1579 October | 307 Tronoy Needles |

| 1580 April | 200 Tronoy Needles |

| 1580 September | 300 tronoy needles |

| 1581 April | 200 tronoy needles |

| 1581 September | 300 tronoy needles |

| 1582 April | 250 Tronoy Needles |

| 1582 September | 310 tronoy needles |

| 1583 September | 200 tronoy needles |

| 1584 April | 200 spanish needles |

| 1584 April | 200 Tronoy Needles |

| 1584 September | 200 Tronoy Needles |

| 1585 April | 2 great steel needles |

| 1585 April | 500 Tronoy Needles |

| 1585 September | 300 tronoy needles |

| 1586 April | 200 tronoy needles |

| 1586 September | 500 tronoy needles |

| 1587 April | 200 Tronoy Needles |

| 1587 November | 250 Tronoy Needles |

| 1587 November | 250 Milan needles of sundry sizes |

| 1588 April | 300 needles |

| 1588 September | 300 tronoy needles |

| 1589 September | 212 tronoy needles |

| 1590 April | 250 tronoy needles |

| 1590 September | 300 tronoy needles |

I noticed that in the April warrant of 1584 both Milan and Tronoy needles were bought, and in the November warrant of 1577, both Spanish and Tronoy needles were purchased; there went the theory that “tronoy” was a synonym for one or the other.

At this point I contacted the two experts I knew of on needlemaking; one, unfortunately, had died since he published his book on the English needlemaking industry, and the other’s email was no longer in service.

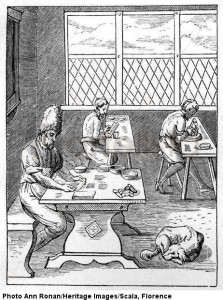

So then I tackled period needlemaking itself. Perhaps, somewhere in some document about the origins of the needlemaking industry, I would find the clue I needed. I learned a great deal about how steel needles were made, about how they were bundled into canvas bags along with oil, soap and chalk powder and rolled between two heavy boards to sharpen them. I learned how the eyes were punched, and the names of some obscure tools specific to the trade, and then….I came across a mention of “train oil.”

“Train oil”, as it turns out, is the anglicization of the dutch “Trann olie”. It is a synonym for sperm whale oil..which was considered one of the best possible lubricants for polishing metal…as well as one of the best possible materials for quenching annealed steel in. After being heated for annealing, plunging needles into oil rather than water allowed them to cool more slowly, making them stronger and eliminating some of the “crooking” or bending of needles that occurred as they cooled.

Traan olie…”tronoy”? Is it possible that this term meant steel needles quenched in whale oil? Had it become a commonplace term in England? Did the local steel needle maker brand his needles that way?

Or was there some dude with the last name of Tronoy selling high-class steel needles in London?

And you know the worst thing about this stumper? It’s my conviction that somewhere out there is a person who would say, “Oh, tronoy needles? They’re ____. It says so in this source…” without blinking an eye. So if you’re out there and reading this, o hypothetical research saviour, drop me a line!

Leave a Reply to Rachel Cancel reply