Clothing the Elizabethan Poor

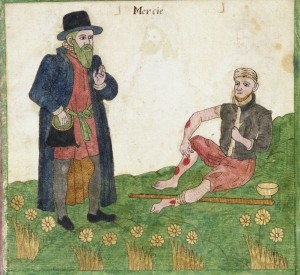

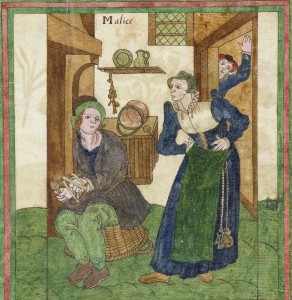

There’s not much available on what the penniless wore in the 16th century. They had hardly anything of value and rarely showed up in pictures of any kind.

Fortunately, there are some sources available. I’ve just put one of them online:

Excerpts from the account books of the Tooley Foundation: Poor Relief in Ipswitch, 1580s-1590s

Ipswitch was lucky to have a generous and civic minded merchant, Henry Tooley, donate his substantial estate to helping the poor of the town when he died. The Tooley foundation maintained hospitals and poorhouses, worked to employ the poor, housed, fed and clothed those with nowhere else to go, and–most admirably of all–kept precisely detailed accounts of what they spent all of their money on.

The records date from the 1580s and 1590s. A variety of clothing items were bought and made for men, women and children at the various houses and hospitals.

Women received the following items, paid for by the Tooley foundation: petticoats, waistcoats, frocks (aka gowns), smocks, shoes, knit hose, aprons, coifs, kerchiefs,leather shoes and neckerchiefs. Men received shirts, doublets and hose, jerkins, ruff bands, knit hose, long coats and leather shoes.

A woman would receive either a “peticote and a wastcote” or “one frocke”, but not both; and for the men, they almost always received “one jerkine and i payre of bryches”, or “one cote”, with doublets mentioned only once. Which raises the interesting possibility that, in this case, a jerkin was either a) a synonym for doublet, or b) worn directly over the shirt.

The fabrics used for these items were cheap and practical. The doublets, hose, coats, petticoats, waistcoats and frocks were made of wool in the entries where a fabric was specified: either russet (the cheap woolen “greaye russett” fabric in this case, a homespun fabric in natural grey or red-brown, rather than the color russet), frieze ( a heavy coat-weight wool),

kersey, plunket or unspecified woolen cloth. Cotton (cheap napped wool) was used for lining hose and jerkins in one entry; linen cloth was specified for lining the “pore chilldrens cottes” in another entry. The bodies of frocks, petticoats and waistcoats were frequently described as stiffened or lined with canvas.

The smocks, shirts, coifs, aprons and linen garments were made out of canvas or fairly heavy-weight, sturdy linens like Oxenbridge linen and Rhone Linen. Large orders of “hempen cloth” followed by account entries for making sheets, shirts and smocks suggest that these items were made from the hemp cloth purchased. Shirt bands and coifs were made out of the finer, but still modest, lockram.

The amounts of fabric used for these garments are also illuminating. 3/4 yard of frieze was used for a pair of hose. 3 1/2 yards of russett were enough to make a coat for Clement Slokam. 3 yards of kersey made a pair of breeches and a jerkin. A smock for Alice Punder took 2 yards of canvas, and smocks for “the grettest wenches” also used only 2 yards of Rhone canvas. Shirts of the same canvas required only 1.45 yards to make, and one ell of coarse oxenbridge linen was enough to line two bodices.

The entries for garments also give hints as to their construction. When lining is mentioned in frocks, coats and petticoats, it is almost always for the upper bodies alone. This confirms that the petticoats were made with attached bodices. Frocks had no lining in the woolen skirts; only the bodices. “Item…ii frokes, the overbodys lynide”…”ii frokes, the bodys lynid”. Jerkins, doublets and men’s hose were also described as lined.

The entries for coifs reference lining coifs with “hamborow” (a cheap linen fabric). A coif took, on average, 1/6 of a yard to make. Coifs were made of lockram and of some sort of checked fabric (“coifs of chekes”), and–somewhat puzzlingly–there’s an entry for inkle (linen tape) for coifs that allocates three yards of inkle per coif…an indication that it was used for more than gathering the coif at the base of the neck.

As for fastenings, a couple of interesting items emerge from the accounts: points and laces were used for the boys clothing, and hooks and eyes mentioned for fastening both petticoat bodies and waistcoats. However, tin buttons were used on the boys coats, and they were attached with leather laces: “for lether lacis to sett on the buttones of the boys’ cotes”.

Also, I find it interesting that knit hose are so prevalent. I’d always assumed that the poorest of the poor wore cloth hose through the end of the 16th century; but, though cloth hose does show up in the accounts, there are more references to knit hose, for both women and men, then for cloth hose.

It’s possible, however, that the women supported by the Tooley Foundation–several of whom were listed as knitters–may have been hired to produce the knit stockings by the foundation as an additional method of poor relief.

In these accounts, the tailors’ charges for making various garments did not include the cost of materials, which lets us gain a clearer idea of the relative time and work needed for items. Petticoats, frocks and long coats all cost eightpence to make, a hint that they involved a similar amount of stitching and were therefore of similar general size. A waistcoat cost fourpence, and probably took half as long to make. A jerkin and breeches cost twelvepence; breeches alone cost between 6.5 to 8 pence a pair.

Given this, is it possible to determine how long an item took to make? The daily wages of the head tailor in Queen Elizabeth’s wardrobe made a shilling per day in the 1590s; the other tailors made twelve pence a day. Interestingly, poor tailors in the Account books of Ipswitch were also described as making 12 pence a day; but account books from Cambridge during the late 16th and early 17th centuries state that tailors could make sixpence, eightpence or twelvepence a day, without specifying what caused the difference in rates.

Leave a Reply to Ruth Newman Cancel reply