Coppers, Kettles and Vats:

Equipment in Early Dyehouses

by Sidney Edelstein

Transcribed from The American Dyestuff Reporter Vol 44, April 1955

[Note from transcriber: additional images of early dyehouses can be found Here].

WHAT did an American dyehouse look like a century and a half ago? Are there any pictures of Colonial dyeing equipment? How were skeins handled? These and many similar questions relating to the actual equipment and technique used by the dyers in the early days of our country have been posed to this writer from time to time. Peculiarly enough, in spite of the publication in many countries of hundreds of books and manuscripts, which have come down to us through the centuries, very few have contained detailed information concerning the equipment used by the dyers, and almost none have contained drawings or engravings depicting the dyer at work in his dyehouse. As far as we have been able to determine, none of these publications actually depicts an American dyehouse nor the equipment used by dyers in the early days of this country. Fortunately, however, several of the oldest books on dyeing published in America do give detailed descriptions of dyeing equipment in use and exact instructions for carrying out dyeing processes with this equipment.

Up until the end of the 18th century, and for at least 2,000 years preceding, equipment used for dyeing throughout the world was of the simplest sort. The equipment used by an American dyer in 1790 did not differ basically from that depicted in woodcuts showing dyeing operations in Europe in the 12th century, in the 16th century or even in the 18th century. Only with the beginning of the industrial revolution did dyeing equipment begin to change. Even so, these changes took place much more slowly than those in spinning, weaving and other textile operations.

In contrast, during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, many improvements were made in the dyeing processes themselves and new dyestuffs and chemicals were constantly being introduced to the dyeing industry. As the New World became more thoroughly explored, many roots, barks and flowers containing coloring matter were examined and brought into use. The introduction of cochineal, the use of tin as a mordant, the manufacture of quercitron from the American black oak, offered new and improved colors which required new techniques. These new colors and techniques, however, were still applied in the same old type of equipment.

Until the beginning of the last century the basic apparatus for dyeing fabrics, skeins or textiles in any form consisted of a simple round vat. These vats were constructed of wood, ceramic, or of metal depending on the availability of specific construction materials. The dyebath itself was sometimes heated in the vat by a surrounding wood fire or furnace or sometimes the water was heated in a separate utensil and then poured into the dyebath. The dyestuffs themselves were prepared in small pots or kettles. Skeins were often dyed by simply hand dipping and turning in the dyebath. Refinements in the handling of skeins consisted either in using hooks to hold the skeins or in hanging skeins on wooden, sticks which were suspended across the dye vat. The skeins were turned by hand or sometimes by additional hooks. In the case of piece goods, the technique did not differ greatly from the handling of skeins. The fabrics were either dipped by hand or pulled through the dyebath over a pole laid across the vat. A special refinement, which was often used, was a simple wooden reel turned by hand over which the goods could be turned in the dyebath.

The few old woodcuts or drawings concerning dyeing, which have come down to us, picture this equipment and the dyer at work. Particularly interesting is the example shown by Singer in his monumental book on alum (1). This drawing, see Figure 1, is from a Florentine Manuscript Treatise on the silk art written in 1458. On the right, silk skeins are being dyed in a typical dye vat heated by a wood fire. The dyers are wearing shoes raised by clogs to keep their feet dry. The dyebath is a typical, evil-smelling one of the times. (Note the dyer at the left is holding his nose.) Washing the skeins and mordanting are being carried on by the other workmen.

The few old woodcuts or drawings concerning dyeing, which have come down to us, picture this equipment and the dyer at work. Particularly interesting is the example shown by Singer in his monumental book on alum (1). This drawing, see Figure 1, is from a Florentine Manuscript Treatise on the silk art written in 1458. On the right, silk skeins are being dyed in a typical dye vat heated by a wood fire. The dyers are wearing shoes raised by clogs to keep their feet dry. The dyebath is a typical, evil-smelling one of the times. (Note the dyer at the left is holding his nose.) Washing the skeins and mordanting are being carried on by the other workmen.

One of the earliest, the most famous, and surely one of the rarest books on dyeing was that published by Giovanni Rosetti in Venice in 1540 (2). While this book went through many editions, only the first contained woodcuts showing dyers at work. These drawings depict the same type of simple apparatus which would have been used by our Yankee "country dyer." Figure 2 shows the dyeing of skeins in unheated vat, which was probably made of wood. A hook used for manipulating the skeins is shown hanging on the wall. Figure 3 shows a typical boiling dye vat heated with a wood fire, and the cloth turned through the bath over a windlass-again the same equipment as was used in this country two centuries later.

Text books and manuscripts are not the only sources of information about ancient trades or crafts. Witness the 16th century German Valentine in Figure 4. In this rare example, the dyer professes his love with such sayings as, "I intend to give a skein of real silk to my sweetheart," and "In order to look prim you have to use my colors," but at the same time he proudly reels his fabric through the dyebath in a typical dyehouse of the time.

As has been mentioned, while several of the early books on dyeing published in this country did not contain any illustrations, detailed information on the equipment and the setting up of a dyehouse are given. From these word pictures, together with the actual pictures we have seen, we can form a satisfactory idea of a typical dyehouse and the equipment used in the early days of our own country. Particularly detailed on this score is the information furnished by Asa Ellis in the first book on dyeing published in the United States (3).

Ellis advises as follows:

"Your dyehouse should be sixteen or twenty feet square; well furnished with light and placed near a stream; water being essentially necessary for preparing your cloths, and for rinsing them when dyed. The floor should be made of leached ashes and it will soon become hard and render you more secure from fire.

"Your copper, or coppers, should be situated near the centre of the house; and the blue vat, about six feet from the coppers, in which you intend to heat the blue die.

"The size of your blue vat will be in proportion to the business you expect. The common size and dimensions are as follow; viz it should be five feet deep, three feet diameter at the top, and twenty inches at the bottom. Place your vat two feet in the earth, for the sake of conveniency; observe that its cover fit close.

"The staves of your vat should be one inch and a half thick, bound with iron hoops. Wooden ones will do, but you will find them more expensive than iron, they will soon fail, and perhaps the vat will spring a leak and you loose your dye before it is perceived.

"It is necessary to have a hoop, with a net stretched over it, that will sink within your vat. This hoop should be suspended about two feet from the bottom of the vat, by four small cords fastened at the top of the vat. The design is to keep your cloth, while colouring, from the grounds, or sedament, which lies at the bottom.

"A dyer's rake is also necessary. It is made in the shape of a churn-dash, with the exception only that it should be a semi circle, or half round. The foot pieces should be about twelve inches diameter, with three or four holes through it, and a stiff handle inserted, five feet long.

"Further, a stick should be put across your vat, about one inch below the surface of the dye, in order to draw the cloth over, when colouring; and you will need two sticks about a foot long with hooks at one end, to hall your cloth, when in the dye; for it will be inconvenient to hall it with your hands. Tcnrer hooks will answer the purpose.

'These directions, for the vat, are the best I know; as it was remarked, you can conform its dimensions to the business, for which you wish to employ it.

"A copper or caldron is necessary for all dyers. The business cannot be carried on without one or more of them. Your largest copper should contain sixty, or seventy gallons. It should be set in a brick furnace; because that will heat your copper sooner. The top of the furnace, which encloses the copper ought to be six inches thick, so that you may plank the brick work, and nail the lip of the copper to the plank and plaister of the furnace. Then your copper, with care, can be kept clean, which is absolutely necessary.

"An iron caldron is very convenient, in a dyehouse to boil Logwood and other dyestuffs; there are many uses, in which it will be employed; the benefit of one would soon pay you for purchasing it. A small kettle will answer but it is inconvenient.

"A reel, or wench is necessary; it is made of a piece of timber two inches square and long enough to cross the copper, with a crank at one end, and four slats or posts, that are incerted in the shaft before mentioned. The reel, thus formed, should be about a yard in circumference. On this, the cloth in the copper is to be turned, while colouring, to preserve it from spotting.

"Many dyers place one end of a board on the edge of the copper to receive the cloth in order for cooling; but it is much better to have a cooling board, about eight feet long and one foot wide placed at a small distance from the copper about waist high. Another about the size of a press-board you may rest on the top of the copper to receive the cloth from the reel; then take the board with the cloth and place it under the cooling-board, where you will be careful to have blocks to rest your cloth on, in order to cool it, by folding it upon your cooling board.

"Those, who intend to dye indigo blue, must have an iron kettle, that will hold a pailful, in order to grind indigo; and an iron ball, of twelve pounds weight; one of eighteen pounds is better.

"Dyers should be furnished with spare tubs and pails; also with steel yards, or scales that are true; in order to weigh dye-stuffs, which ought never to be used without strict attention to their weight. There are but few exceptions to these rules."

Now obviously the equipment for dyeing in an early American dyehouse was of the simplest. The techniques for carrying on the various dyeing processes themselves were often quite complicated, however, and required the greatest of skill in manipulation by the, dyer. In fact, in those days the dyer had to accomplish by his skill and agility what we often do today through the use of specially designed dyeing equipment and mechanical aids.

A realization of the skill required by these early dyers in using their very simple equipment can only be realized when we examine the actual details by which they carried on a particular dyeing operation. The early dyers had many dyestuffs and could produce a wide variety of shades. Of all the dyeing processes which the dyer had available, perhaps the best known and at the same time the most complicated was the dyeing of indigo. The dyer of indigo had to have not only highly developed manipulative skills but what amounted to a special intuition in order to recognize the many critical signs which indicated possible changes in the indigo bath. If the dyer did not heed these signs properly and at the right time, many days could be lost and dyestuffs and chemicals of considerable value wasted. While each dyer had many pet methods for preparing an indigo vat, these all depended on a careful reduction of the indigo by a fermentation process. Even with the variations in formulas from one dyer to another, they were all essentially the same and depended on a great deal of experience. Again we turn to Ellis (3) for typical instructions in preparing an indigo vat and for carrying on the dyeing.

"RECIPE FOR THE BLUE DYE, OR INDIGO VAT"

"As before observed, the side of your vat will be in proportion to the business, in which you would employ it. In order to set, or raise a new dye, put one pound and a half of Indigo into an iron kettle, which will contain two or three gallons. Then fill your kettle with river, or pond water, wash the Indigo and pour off the water; then take a pestle and beat the Indigo so small that a cannon ball will run upon it. Add a point of urine to the Indigo thus preparing for grinding; then place the kettle on your knees and let the ball run on the Indigo until it be ground to a paste; observe occasionally to scrape down with the knife, the Indigo, which adheres to the sides of the kettle, lest you should waste it.

"If your Indigo be too dry add a little more urine. It should be sufficiently moist that the ball may roll freely; but not so thin as to slop over. This process of grinding should be continued about half a day. The Indigo being thus prepared may be sit aside for the present. Your vat is, in the next place, to be put in order. First, it should be about half full of boiling water; then put in a pound and a half of good potash dissolved in hot water; to this add twelve quarts of wheat bran; after sifting out all the flour or kernel, sprinkle it into the vat with the hand and stir the dye with the rake. This done, add twelve ounces of good grape Madder, then with the rake mix it well with your dye. In the next place take the Indigo you have ground, nearly fill the kettle with warm water; keep the ball rolling, while the kettle is filling, and let the ball run until the Indigo is well united with the water; then let it stand and settle for two or three minutes, then pout the water that is on the Indigo, into the vat. Be careful that none of the sedament at the bottom of the kettle is turned off with the water; this must be ground again and more warm water added and poured off, in the manner just described, until the Indigo is nearly all desolved.

"Observe, through all this process, your vat must be closely covered, excepting the time that is necessary to introduce the ingredients.

"When you have poured in all your Indigo, which is the last article, you will do well to stir up the dye, with the rake; then cover your vat, if possible to exclude the circulation of the air. Let your vat, thus confined, remain for eight or nine hours before it be opened.

"Half a pail-full of grounds from an old vat, that is in good order, might be useful as the first article introduced into a new one. However, in fitting a new vat, the evening is the best time, having all the materials, we have mentioned, introduced by the hour of ten at night. Then your dye may rest till the morning; when you should open the vat and plunge your rake from the top to the bottom of the dye. This should be done with activity and exertion. Bubbles will appear and by repeating the plunges six or seven times, if a thick blue froth rises on the surface of the dye, which is called the head, continuing to float, and further if it put on the appearance of a darkish green; the dye may be pronounced in a good state and is fit for colouring. Perhaps, the process of plunging must be repeated two or three times; but remember every time, after you have plunged your rake in the dye to cover your vat closely, and to let it rest for an hour between these trials. If your dye becomes cool, it will not rise to a head, though it be good.

"If the dye becomes cool it must be heat again. This will retard business and cause trouble. If the dye when first opened, in the morning, appear of a pale blue cast, instead of a dark green, an handful or two of madder must be sprinkled into the vat.

"The dye in the morning after it is set, should be so warm that you cannot bear your hand in it longer than one minute. If the dye appear of a pale indifferent colour, and a whitish scum rises on the surface, it does not work and will not color. In this case, the dye must be heat, and a small portion of all its ingredients must be added; also a handful of stone lime should be put to warm water, and after settling pour off the lime water, into the vat.

"Many through want of better instruction, will frequently look into the vat, to discover the state of the dye. By thus exposing it to the air it cools, and they will never bring it to a head until they are taught better.

"Of all dyes, the blue is the most difficult and must be attended, with the greatest care. After the vat is set and comes to a head, it may stand secure until employed for dyeing cloth. When the cloth is ready for coloring, the dye must be heat.

"If you have sixty yards of flannel, that is so many yards of cloth after it has been scoured, or one quarter fulled; two pounds of Indigo ground with the ball according to our former directions must be put into the vat. together with the proportionable additions, of Potash, Madder and wheat bran.

'The dye should be raised within three inches of the top of the vat.

"Let the vat be hot at night when you leave it: To preserve the heat, enclose the vat with a number of yards of cloth, that it may be sufficiently warm in the morning. At that time when you open it plunge your rake in the dye, then cover it closely; rest one hour then plunge again, repeat these operations two or three times. If the dye be in a good state and work well, there will be as many as ten or twelve quarters of froth or head, floating on the surface of the dye, whose color will appear of a beautiful dark blue; at the same time, the body of the dye will give you a dark green. This is the proper state of the dye, for colouring; or when the dye ought to be employed.

"The cloth should be cleansed from all filth; especially grease; for grease will overset the dye even in its best state. Also everything should be prepared when the liquor is in readiness. So soon as the vat is opened, the head or froth should be taken off and put into a vessel that will contain it, next the net should be let down, and the stick, or cross, placed about one inch below the surface of the dye for the purpose of haIling the cloth over it.

"In the next place, the cloth is to be taken from hot water, being well drained, which process must be observed every time of dipping; hall the cloth into the vat, beginning at one end, keep it open, until you have drawn the whole piece into the dye. Persevere in halling backwards and forwards from one end to the other for twenty minutes; at the same time it should be entirely in the dye. After this process you should begin at one end of the cloth, bring it up and take it on the folding board, and fold it over until it becomes blue and even; for if this process be neglected your goods will be spotted.

"The cloth when first taken out of the vat will exhibit a green shade; but being exposed to the air will become blue.

"Dip the cloth twice; then take out the cross and net; put back the froth, or head, which was taken off. Stir your dye and plunge your rake in it; then close the vat for an hour. After that proceed as before, until the color you wish is obtained,

"The cloth must now pass a second milling. In the meantime, it will be well to prepare your vat to receive the cloth for the last time. Put four or five pounds of woad, well powdered, into the vat. This will save Indigo and render the colour brighter. The woad should be put into the vat, once, in two or three times

of colouring, that is after the dye has done work, or when the dyer has done using it for that time.

"After this the dye should be kept close until it is re-heat for another colouring. The dyer must be careful in hot weather to heat the vat once in a month or six weeks to preserve it. He must also take off the maggots which will appear on the vat above the surface of the dye.

"When the liquor becomes thick and glutenous, by use, the dye must be boiled, the scum taken off and the dye returned to the vat. At the same time add a little lime water, to clarify the dye and settle the grounds; for if the sedament rise the colour will not be good.

"The dyer should never dip his goods, until the grounds are well settled."

After reading over this complicated technique of 150 years ago for preparing an indigo vat, we must smile when we think of how easily we prepare such vats today by the use of hydrosulfite and alkalies. The addition of bran, urine and other materials may seem unscientific, foolish, or perhaps even the result of superstition. The true facts are far from this. The use of these natural materials were necessary and each material had a particular function. The dyer in effect had to act as a bacteriologist without knowing anything about bacteria, for the proper preparation and use of an indigo vat depended on close control of fermentation processes. The indigo had to be solubilized in order to be suitable for dyeing. In order to be solubilized the indigo had to be reduced or in other words "de-oxygenated." In the early days, the only satisfactory method for carrying this on was by a fermentation process wherein the required reducing conditions were set up. Both bran and madder as well as urine each contributed its own ferments and bacteria. One fermenting ingredient might give quick reducing action and then lose its power whereas another material might be slower but last longer. Hence the use of a combination of natural ingredients which would contribute various ferments to the bath. Only through long experience could a vat dyer tell when conditions were right. To plague him even more, the natural materials such as bran and madder varied from lot to lot in their fermenting power. An indigo vat had to be nurtured and tended as carefully as one might a child. The vat required the dyer's constant attention and care. No vat dyer of the old days could listen to a five o'clock whistle. In fact, the dyer's living quarters often were attached to the dyehouse so that he could constantly watch his vat and keep it in "the best of health."

While unquestionably the indigo or woad bath was the most difficult to prepare and required the most care in its use, the early dyer still had to use a consider-able amount of skill and care in dyeing with other dyestuffs. The dyer was constantly beset with the fact that his dyestuffs and chemicals were not uniform and he had no scientific methods for testing. In addition, lack of mechanical aids and unsatisfactory methods of heating necessitated great skill in manipulating fabrics or yarn so that the dyestuffs would go onto the goods evenly and without spotting. Even with "simple" dyeings it is easy to see how the dyer of years gone by might well charge prices for his dyeings far in excess of what he would charge today.

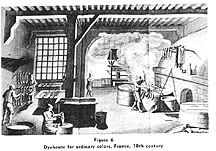

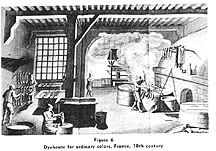

Towards the end of the 18th century, in France, some dyeing establishments began to reach great size. In some of these factories, each individual type of dyeing was carried on as a separate operation with its own dyers, helpers and its own particular dyehouse. In the great Gobelins works, individual dyehouses were set up which were devoted exclusively to indigo dyeing of fabrics; indigo dyeing of skeins; the dyeing of blacks; and the dyeing of light colors. Even separate rooms for washing fabrics and for preparing dyestuffs were maintained. Special means for pumping water and highly developed heating systems for the dyebaths were in use. Nevertheless, even in this great establishment, the dyeing equipment itself was basically the same as that used by the poorest "Yankee Dyer" in this country. See Figures 5 and 6.

Not until about the end of the 19th century did American dyehouse equipment equal and then begin to surpass that of Europe. In the present century the American dyer is no longer at the mercy of his equipment, but because of it he can accomplish great feats of high production and low cost. His "country cousin" of a century and a half ago would not have believed that such things could be possible. The dyeing machines of today would have appeared just as unlikely and fanciful to the old dyers as did one ancient's dream of angels preparing his colors and tending his vats while he slept peacefully beside his wood fire. See Figure 7.

REFERENCES

(1) Singer, Charles, "The Earliest Chemical Industry", London, 1948.

(2) Rosetti, Giovanni, "Plictho De Larthe De Tentori Che Insegna Tenger Pani Telle Banbasi et Sede si Per Larthe Magiore come per la Comune" (How to dye cloth, linen, cotton and silk by the great and common art), Venice, 1540.

(3) Ellis, Asa, Jr, "The Country Dyer's As-sistant", Brookfield, Mass, 1798.

(4) "The Art of Dyeing Wool, Silk and Cotton", London, 1786.

(5) Schiffermueller, Ignatz, "Versuch Eines Farbensystems". Vienna. 1772.

Back to the Dye Woorkes The few old woodcuts or drawings concerning dyeing, which have come down to us, picture this equipment and the dyer at work. Particularly interesting is the example shown by Singer in his monumental book on alum (1). This drawing, see Figure 1, is from a Florentine Manuscript Treatise on the silk art written in 1458. On the right, silk skeins are being dyed in a typical dye vat heated by a wood fire. The dyers are wearing shoes raised by clogs to keep their feet dry. The dyebath is a typical, evil-smelling one of the times. (Note the dyer at the left is holding his nose.) Washing the skeins and mordanting are being carried on by the other workmen.

The few old woodcuts or drawings concerning dyeing, which have come down to us, picture this equipment and the dyer at work. Particularly interesting is the example shown by Singer in his monumental book on alum (1). This drawing, see Figure 1, is from a Florentine Manuscript Treatise on the silk art written in 1458. On the right, silk skeins are being dyed in a typical dye vat heated by a wood fire. The dyers are wearing shoes raised by clogs to keep their feet dry. The dyebath is a typical, evil-smelling one of the times. (Note the dyer at the left is holding his nose.) Washing the skeins and mordanting are being carried on by the other workmen.