Inventories, Warrants, Gifts and Day Books: the underpinnings of Queen Elizabeth’s wardrobe

I have just begun my two week photography blitz at the National Archives.

There’s a lot there to photograph. My goal? To obtain photographic copies of all records relating to Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe that I don’t already have copies of, and to eventually transcribe them all and add them to Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Uploaded database.

The National Archives has changed dramatically in the 12 years since I’ve been there. Their document ordering system has evolved from slips of paper to the swipe of a card and a few clicks on a keyboard. And they now have photography stands available, which allowed me to tear through 1,563 photographs in seven hours! (My back doesn’t thank me, but I’m sure that posterity will.)

There are a lot of documents out there–a huge amount–and a lot of them are pretty obscure. So this is a post about that information: the inventories, warrants, day books and other surviving pieces of documentary evidence left by the blessedly bureaucratic clerks of Elizabethan England. What they are, what they contain, and how you can find them.

Wardrobe Inventories

Anyone who’s reached a certain point in their research of 16th century dress has acquired a copy of Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d, by Janet Arnold. As well as being a masterpiece of scholarship, It contains the combined transcription of three inventories of Queen Elizabeth’s wardrobe taken at (or a few years after) the time of her death.

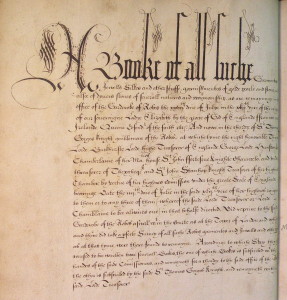

The Stowe Inventory at the British Library (and the copy of it held at the National Archives, LR 2/121) and the smaller companion inventory kept at the Folger are one of the best known sources of information to modern costumers; largely because Arnold’s book is centered around it, drawing material for much of what she tells us about Queen Elizabeth’s Dress. And it is a staggering tribute to sartorial genius: 99 mantles, 67 french and round gowns, a hundred loose gowns, and kirtles, petticoats, farthingales, safeguards and cloaks by the gross. All of it described in loving detail that fires the imagination:

The Stowe Inventory at the British Library (and the copy of it held at the National Archives, LR 2/121) and the smaller companion inventory kept at the Folger are one of the best known sources of information to modern costumers; largely because Arnold’s book is centered around it, drawing material for much of what she tells us about Queen Elizabeth’s Dress. And it is a staggering tribute to sartorial genius: 99 mantles, 67 french and round gowns, a hundred loose gowns, and kirtles, petticoats, farthingales, safeguards and cloaks by the gross. All of it described in loving detail that fires the imagination:

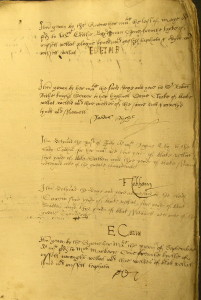

Item one rounde gowne of cloth of siluer wrought with purple and yellowe silke laide aboute and downerighte with a brode passamaine lace of venice golde and siluer with buttons and loupes of like golde siluer pipes and small seede pearle.

Although these inventories are wonderful for providing a look under the skirts of the Queen’s wardrobe at a particular point in time and have provided an invaluable amount of documentary evidence,their snapshot nature prevents them from illuminating other aspects of the Queen’s wardrobe. Such as: how did it change? How did her color and style preferences shift over the years? How was everything made? How much of what materials were used? What percentage of her wardrobe was made new, vs. altered from older garments? To answer these questions, we turn to:

Wardrobe Warrants

The warrants are the workhorse of Elizabeth’s wardrobe records. They are full of information about countless aspects of Elizabethan court life and dress. To understand them, though, we first need to know a bit about how the whole paper trail of Elizabeth’s Royal Household worked.

Because the materials and fabrics used by the wardrobe were so expensive–a velvet gown, in the 16th century, was the equivalent of a wearable ferrari–everything had to be kept track of. Whenever a garment was made or altered for the queen, the wardrobe clerk added a record to the ongoing record book describing the garment, what was done to it, and how much fabric of what kind was used, at what cost. When supplies were bought from drapers, clothiers and haberdashers, this too was noted: exactly how much of what kind of trim was purchased, and how much it cost. Even the linen used to make laundry bags made it into this comprehensive list. Any carpentry work or ironwork done on the coffers and chests that held the wardrobe’s clothing, the work needed to carry clothes back and forth from the wardrobe to the castle–all of this was carefully noted in the records of the Wardrobe of Robes. The clothing and shoes dispersed to poor women on Maundy was also listed.

And that’s not all. There was also the Wardrobe of Beds, which kept track of cloth and supplies used to make furniture, curtains, beddings, and other household textile goods. Stable warrants recorded every bit of leather, fabric and metal used to make caparisons and tack for the hundreds of royal horses: both working horses, like those used to carry supplies on progress, as well as the coursers and steeds for ladies and gentlewomen.

Any clothing made for the queen’s servants were also described and the amount and type of cloth used carefully noted: livery for yeomen, coachmen, littermen, footmen, gentlemen of the privy chamber, gentlewomen of the bedchamber–all received payment in part with cloth or clothing, and all of them ended up in the records. Many of these boilerplate warrants were called “warrant dormants”, which were written up and filled in with names and particulars when they were put to use. Give to _______ ___ yards of black satin for livery.”

The queen’s heralds and pursuivants were also dispensed clothing and cloth from the royal wardrobe store. And any time a lord was made a member of the order of the Garter, a set of garter robes was made up for him–all recorded in dutifully loving detail in the wardrobe clerk’s notes. Linen for the chapel alter and the choirboy’s robes? Hangings for the parliament chamber? These too were written up. Even clothing made for prisoners in the Tower of London, and clothing and furnishings made for visits by foreign royalty, make an appearance in the warrants.

And then there’s the one-offs. If a courtier or some other people was given a gift of a gown, or cloth for a gown, by the queen, a warrant would be written up and signed by her or one of her functionaries, to be delivered to the wardrobe staff. These warrants were also frequently transcribed into the clerk’s book; though sometimes they weren’t.

Let’s not forget the Revels Warrants for the plays and theatrical performances put on by the court. Although Elizabeth perferred plays, there were still tailors and artificers tasked with building the sets and costumes for various productions put on during the holidays, and their expenses, like those of the Wardrobe of Robes and Beds and the Stable, were catalogued in detail.

Needless to say, the 500+ large pages of paper ordered by the wardrobe every six months (with their purchase noted in the records) did not go to waste.

So: Wardrobe of Robes warrants. Maundy warrants. Livery warrants. Warrants Dormant. Stable Warrants. Revels Warrants. Warrants for the Order of the Garter. Warrants for Heralds dress. Warderobe of Beds warrants. Warrants for the chapel and parliament chamber. Still with me?

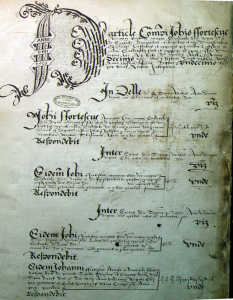

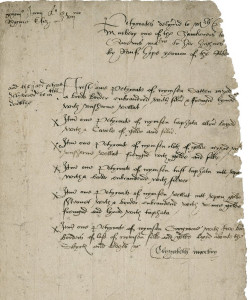

If you are, and if you want a look at some of these toothsome documents, you’re in luck. Every year, the working copies kept by the various wardrobe clerks for all of these departments were carefully transcribed into a bound book, in full detail; all of the information described above was included. (Aside from the Revels warrants.) The copies were signed by the clerk or assigns, and these books, due to a wonderful stroke of fortune, are available to us today at the National Archives. They are LC 9/53, the warrant for 1558-1559, through LC 9/95, for the last year of Elizabeth’s reign.

If you are, and if you want a look at some of these toothsome documents, you’re in luck. Every year, the working copies kept by the various wardrobe clerks for all of these departments were carefully transcribed into a bound book, in full detail; all of the information described above was included. (Aside from the Revels warrants.) The copies were signed by the clerk or assigns, and these books, due to a wonderful stroke of fortune, are available to us today at the National Archives. They are LC 9/53, the warrant for 1558-1559, through LC 9/95, for the last year of Elizabeth’s reign.

The catch? They’re in Latin. All of them. So if you do want to find out exactly how much material was used for a petticoat in 1570, or who the ladies of the bedchamber were and how much fabric they received, you’re going to have to reach for that Latin Dictionary.

But don’t lose hope! these yearly compilations were themselves condensed and transcribed into english, and these documents, too, are at the National Archives. LC 5/32 holds the qcollected warrants for Queen Elizabeth’s reign up to 1560; LC 5/33 has 1560-1567, LC 5/34 1567-1575, LC 5/35 is 1575-1585, LC 5/36 is 1585-1593, and LC 5/37 is 1593 through the end of the reign.

But don’t lose hope! these yearly compilations were themselves condensed and transcribed into english, and these documents, too, are at the National Archives. LC 5/32 holds the qcollected warrants for Queen Elizabeth’s reign up to 1560; LC 5/33 has 1560-1567, LC 5/34 1567-1575, LC 5/35 is 1575-1585, LC 5/36 is 1585-1593, and LC 5/37 is 1593 through the end of the reign.

Although the sense remains, the detail of the english warrants doesn’t match that of the Latin warrants. The English transcription also discards some of the livery information, such as the fabric given to the gentlemen of the privy chamber and the gentlewomen of the bedchamber.

For example, a Latin Warrant of 1568, in LC 9/60, has the following:

To Walter Fish for making a gown of the french fashion of murrey tissue welted with murrey velvet…the edges edged with fringe lace of gold and silver of our store, lined with crimson sarcenet with bayes in the pleats, with vents of fustian and frieze in the ruffs of our great warderobe. 40 shillings. For 8 yards of crimson sarcenet for lining the same at 6 shillings the yard. For 2 yards of baies for lining the pleats at 4 shillings the yard For a yard of fustian for the vents 16 pence for 7 yards of frieze for lining the ruffs 12 pence

While the English transcription from LC 5/34 reads:

To Walter Fyshe our Tayler for makinge of a Frenche gowne of murrey Tissue welted with murrey veluet of our store…laied on the edges with Frindge lace of gold and siluer lyned with Crimsen Sarcenet and baies in the plaites with ventes of Fustian and frize in the ruffs of our great warderobe.

And these English transcriptions of the Latin transcription? The 1568-1585 warrants from the LC series were themselves transcribed into a larger volume, now called MS Egerton 2806. This book, combined with the Stowe Inventory, forms the backbone of Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d, and together are the source for the great majority of the primary evidence contained in the book. This is browseable online as well.

New Years Gifts

Not everything the queen wore was made by her artificers. The traditional New Years’ Gift Exchange was also an avenue into the wardrobe. Usually courtiers gave the Queen gold coins in a decorated pouch, but some gave her items of clothing: smocks, partlets, sleeves, handkerchiefs, scarves, petticoats, foreparts. Most of the gifts were smaller items of clothing, suited to being highly decorated but not requiring a real fit. Some of these garments were accepted and worn; others were accepted and kept for years without seeing any use, until they were listed in the posthumous inventory of Elizabeth’s wardrobe as

Not everything the queen wore was made by her artificers. The traditional New Years’ Gift Exchange was also an avenue into the wardrobe. Usually courtiers gave the Queen gold coins in a decorated pouch, but some gave her items of clothing: smocks, partlets, sleeves, handkerchiefs, scarves, petticoats, foreparts. Most of the gifts were smaller items of clothing, suited to being highly decorated but not requiring a real fit. Some of these garments were accepted and worn; others were accepted and kept for years without seeing any use, until they were listed in the posthumous inventory of Elizabeth’s wardrobe as

“Item one foreparte of white Satten embrodered allover with venice gold syluer and Carnacion silke in squares and flowers Chevernewise unmade.”

We don’t have a full record of all the New Year’s gifts received by the queen. The records, one roll per year, are now scattered about the globe; A couple at the National Archives, one at the Folger Library, and one even turned up in the Dallas Public Library. Some of them have been made available online. And thanks to the Herculean research and saintly persistence of Jane Lawson, the information from all known Gift Rolls–26 of them–are gathered together in her recently published book,The Elizabethan New Year’s Gift Exchanges, 1559-1603

The Day Book

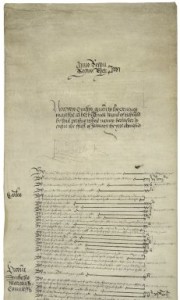

Another record exists of what went on in the wardrobe: specifically, how items left the wardrobe. a single existing Day Book remains from the wardrobe of robes, containing detailed records of all gowns and cloth given out of the wardrobe (usually to one of Elizabeth’s Gentlewomen of the Privy Chamber or Maids of Honor) as well as a listing of each and every item found missing from one of her garments. Given the number of pearls, spangles and jewels loaded on gowns like her “frenche gowne of riche golde tissue with a border of purple satten allouer enbrodered with…pearle lined with purple Taphata”, these entries were frequent: buttons, pearls, jewels, hairpins, aglets, all of them accidental largesse distributed by the queen during her daily round. This document is also in the National Archives, listed as C 115/91, and published by Janet Arnold as Lost from her Majestie’s Back.

Another record exists of what went on in the wardrobe: specifically, how items left the wardrobe. a single existing Day Book remains from the wardrobe of robes, containing detailed records of all gowns and cloth given out of the wardrobe (usually to one of Elizabeth’s Gentlewomen of the Privy Chamber or Maids of Honor) as well as a listing of each and every item found missing from one of her garments. Given the number of pearls, spangles and jewels loaded on gowns like her “frenche gowne of riche golde tissue with a border of purple satten allouer enbrodered with…pearle lined with purple Taphata”, these entries were frequent: buttons, pearls, jewels, hairpins, aglets, all of them accidental largesse distributed by the queen during her daily round. This document is also in the National Archives, listed as C 115/91, and published by Janet Arnold as Lost from her Majestie’s Back.

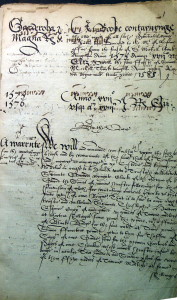

Miscellaneous Warrants

These are found everywhere, in a variety of manuscripts. A good number are collected at the British Library in MS Add 5751a: Individual, one-page warrants directing the queen’s tailor to make gowns for her Maids of Honor, or a night gown for her favorite, the Earl of Leicester, or to make six petticoats of various rich crimson fabrics. The content of some of these individual warrants may show up in abbreviated form in one of the Latin or English compiled wardrobe accounts; or they may not.

These are found everywhere, in a variety of manuscripts. A good number are collected at the British Library in MS Add 5751a: Individual, one-page warrants directing the queen’s tailor to make gowns for her Maids of Honor, or a night gown for her favorite, the Earl of Leicester, or to make six petticoats of various rich crimson fabrics. The content of some of these individual warrants may show up in abbreviated form in one of the Latin or English compiled wardrobe accounts; or they may not.

Letters

And finally, there is correspondence. Nuggets of information on Elizabeth’s wardrobe can be found here, though truly interesting information is rare. The well known letter from the young Elizabeth’s nurse to the King begs him to give her charge money for apparal,

for she hath neither gown, not kirtle nor sleeves, nor railes, nor body stitchets, nor handkerchiefs, nor mufflers nor biggins.

In 1577, Sir Amias Paulet sent Walsingham a letter mentioning that he

Sends a farthingale such as now used by the French Queen and the Queen of Navarre

…most likely a french farthingale, which first makes its appearance in the Queen’s wardrobe accounts three years later.

There are always more bits of information showing up here and there…but the above sources are the main ones available for serious students of dress. My goal to provide complete coverage of Elizabeth’s wardrobe throughout her reign is progressing; some of the inventories from the end of her reign are available, as are copies of the warrants from 1568-1593. I’m currently working on finishing a transcription of the 1593-1603 warrants, and will then turn to the beginning of her reign and transcribe the warrants from 1558-1568.

And then? Get a copy of the full Stowe Inventory and the Day book transcribed, as well as all of the wardrobe records relating to the Queen’s coronation; and then, perhaps, I’ll start on some of the Latin accounts.

All of which will be in my camera by the time I leave England…

Leave a Reply