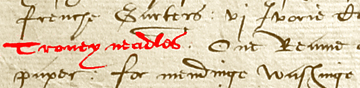

Tailor from the Nürnberger Zwölfbrüderstiftung manuscript, c. 1601

If I was a tailor in 16th century London, how many days’ or weeks’ worth of pay would three yards of kersey cost me?

It’s a difficult question to answer. For one thing, professional tailors usually received payment on a per-item basis, rather than receiving a “salary” or “wage” as we know it. For another, the sources I’ve found are usually specific to a particular time and place, and wages varied widely over the 16th and early 17th century.

I will be throwing shillings and pence about with abandon as I continue, so a quick refresher on English money in the 16th century: 12 pence equaled 1 shilling, and 20 shillings equaled £1.

One place where tailors were employed by the day, rather than by the piece, and employed for a number of years, was in the Royal Office of the Revels. A legion of tailors, painters, carpenters, leatherworkers and other artificers were needed to create the dazzling costumes and sets of revels and masques put on by Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth. Although the number of revels staged decreased during Elizabeth’s reign, due to her preference for theatrical performance over the elaborate allegorical revels and masques preferred by her predecessors, tailors’ wages continued to be recorded through the end of the 1580s.

Feuillerat’s Documents Relating to the Office of the Revels in the time of Edward and Mary and Documents Relating to the Office of the Revels in the Time of Elizabeth, aka “The Loseley Mansuscripts”, describe a great deal about the revels and the clothing made for their participants. They also describe the tailor’s wages paid for the work. (1)

A fairy costume for a masque. Designed by Inigo Jones, 1611. Although this costume dates to several decades later than the revels of the 1560s and 70s, it was similar in style to those of earlier decades.

In 1548, 32 tailors were hired to work on costumes and stage properties for King Edward’s Shrovetide revels. The foreman was John Holt, yeoman; he received 9 pence a day for his pay. The other tailors all received 8 pence a day. They worked anywhere from 3 days and 2 nights to eight days and two nights, receiving an additional 8 pence for each night worked, as well as 8 pence for each day. One can imagine the frenetic activity of all of these men working late into the night, struggling to thread needles by candlelight, all to make the Shrovetide deadline.

In addition, as an officer, foreman John Holt was allowed “dieting charges” of two shillings a day. The other officers–master of the revels Sir Thomas Vaverden, the Clark comptroller John Bernard and the clerk, Thomas Phillips–were the only others who received this extra pay.

John Holt was also recompensed for charges out of his own pocket during the work. He hired a wagon and a barge on Shrovetide from Blakfriers to Greenwich to carry all of the masks and clothing to the location of the revels, and hired the same on Ash Wednesday to carry them back to Blackfriars. He also paid for 48 candles and candlesticks for them, needed for working by night, as well as for pack needles and thread. In all he laid out 28 shillings of his own money–a significant amount.

For the following Christmas revels of 1548, however, John Holt received only 8 pence a day–the same as the rest of the tailors. He still received his additional 2 shillings a day, and, as before, presented a bill for money he had laid out red and white wool, carriage of revels stuff to the site where the performance was held and back again, and for a considerable amount of thread.

He received 10 pence a day for the 1549 revels, while the other tailors received 7 pence; and, by 1550, he was listed as “John Holt, yeoman, Cutter at 2 shillings the day and 2 shillings the night”, with his dieting charges no longer mentioned. He continued to pay for all manner of things out of his own pocket during preparation of a revel: He paid to hire an Irish Bagpiper for one, and for making a dragon with seven heads for another.